Introduction

Daily mobility is based on the concept of an inclusive city, i.e. a city that aims to reduce social and spatial inequalities caused by an urban mobility model that does not respond to people’s differentiated needs – especially the more vulnerable groups – and who are therefore at risk of being excluded from job opportunities, socialisation and the use of public spaces.

For many years, inclusive mobility was included in the priority policies of a number of European cities, Highlighting the social aspect of transport, as well as the generation of inclusive public spaces that foster social cohesion. In this regard, for the last 20 years, Barcelona has been implementing actions focused on improving accessibility on public spaces, so that people with functional diversity can go about their daily lives and enjoy public spaces with autonomy. Going one step further, the city has also taken on a commitment to work towards a city model that places the sustainability of life at the heart of its policies, where spaces are adapted to the needs of people rather than people having to adapt to the conditions existing in those spaces.

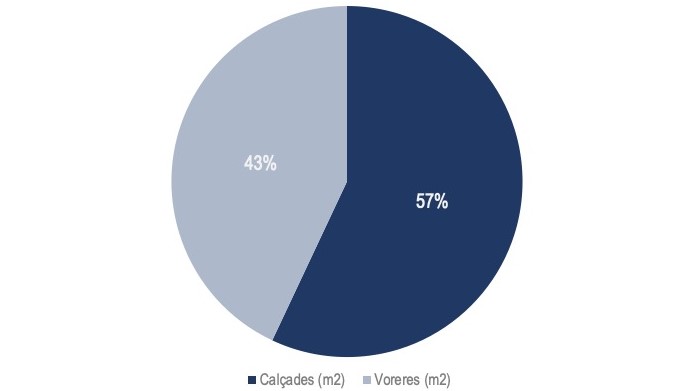

Barcelona is now a walkable city, where nearly 35% of city journeys are made by walking. However, over half the public space is occupied by motorised vehicles (moving and parked). In relation to their capacity for moving people, cars are the mode of transport that takes up most space. If this is extrapolated to the intensity of use of Barcelona’s streets and squares, it can be seen that each city resident has approximately 4 m2 of pavement, while each vehicle has 12 m2 of roadway (see Ilustration 1).

Therefore, based on the importance of the comprehensive well-being of city residents, their personal autonomy and the quality of their lives throughout their life cycle, this study aims to carry out a preliminary territorial approach on the conditioning factors for everyday mobility, on a city-wide scale. Creating a preliminary picture of what goes on in the city may be the start of a more complex and detailed study that will make it possible to work towards a mobility based on the joint responsibility of three factors: inclusion, care and health. .

Everyday mobility

In Barcelona City Council’s Urban planning manual for everyday life Urban planning with a gender perspective , mobility is defined as one of the key factors in the formalisation of cities, and in the organisation of activities to facilitate people’s everyday lives. It is an essential and independent part of the urban fabric’s configuration, along with the uses given to buildings, including housing and facilities.

The facility, autonomy and security that people need to access the various places used for socialising means that everyday mobility also has a crucial role to play in the vitality and resilience of a city’s social fabric. For senior citizens and people with reduced mobility, especially those with physical limitations, having access to meeting and community spaces near their homes is a determining factor for their emotional and physical well-being.

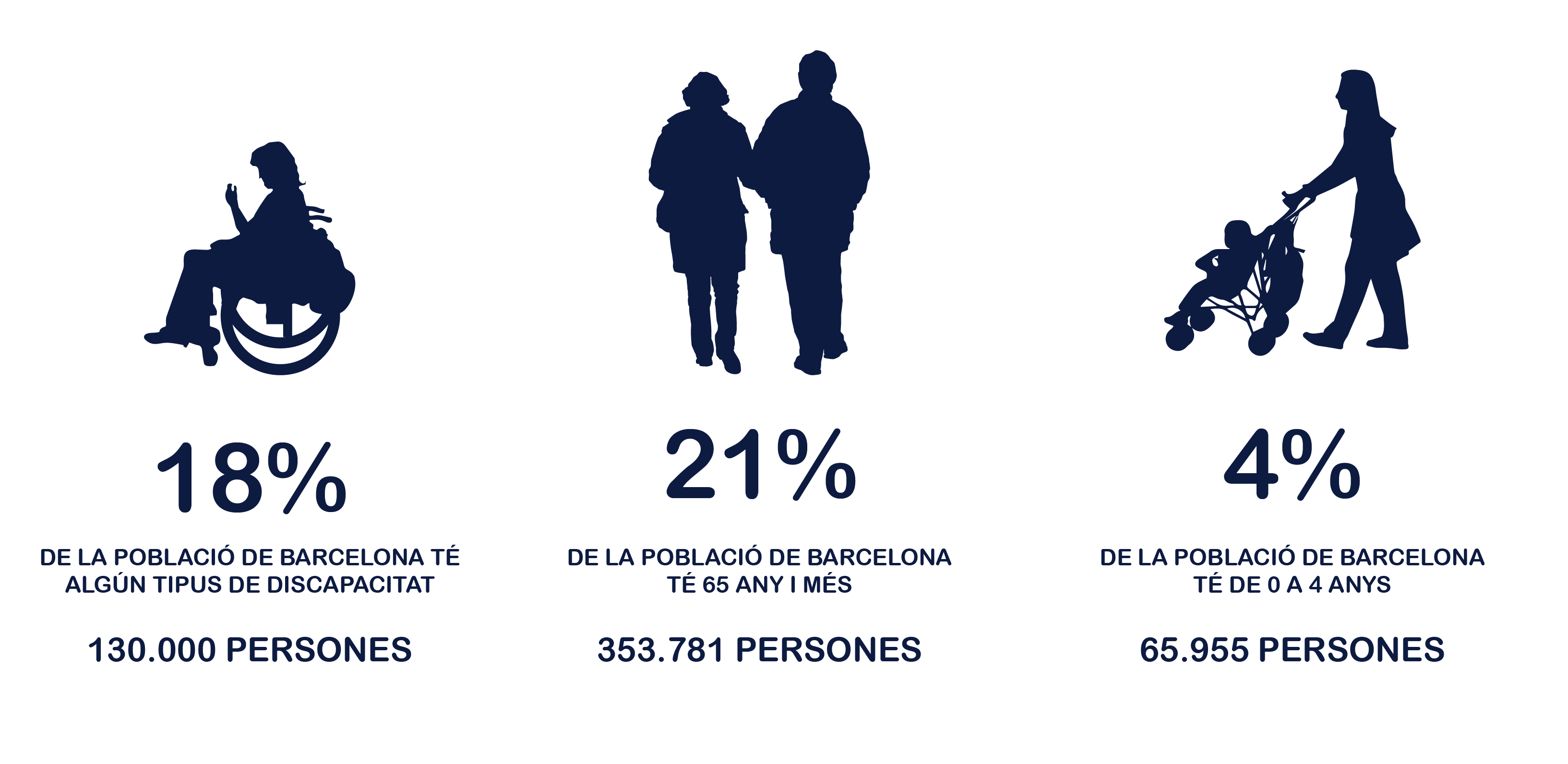

For people aged 65 and over, travelling safely and autonomously on foot enables them to take part in their neighbourhood’s social network, reducing possible situations of loneliness, while also enabling them to age in an active, healthy way. This is important if we take into account that in Barcelona, the population of people over the age of 64 is steadily growing, and projections indicate that if the current trend continues, this demographic group will account for 25% of the city’s total population by 2030, compared with the current 21.5%. According to Barcelona’s municipal register, in 2018 there were 349,922 people over the age of 64 living in the city, nearly a fifth of its total population, and 25% of them lived alone1. The proportion of women gradually increases with age, so that the proportion of men aged over 64 is 18.2%, while the proportion of women rises to 24.3%2.

Meanwhile, children – mainly younger ones (from 0 to 4 years old) – are also sensitive to factors that condition everyday mobility. For example, their needs when travelling on foot include the presence of people to look after them and prams or pushchairs. According to the study Young children and families in Barcelona (Institute of Infancy, 2010), the most likely scenario is a mother accompanying one or two children with a pushchair, because although nearly 80% of children live in a conventional two-parent household (mother-father), mothers dedicate 19 more hours a week to looking after children under the age of 6 than fathers. 86% of single-parent households consist of a women with children.

2 Barcelona Public Health Agency (2019) Health in Barcelona 2018, Monographic: Living and health conditions of senior citizens in Barcelona

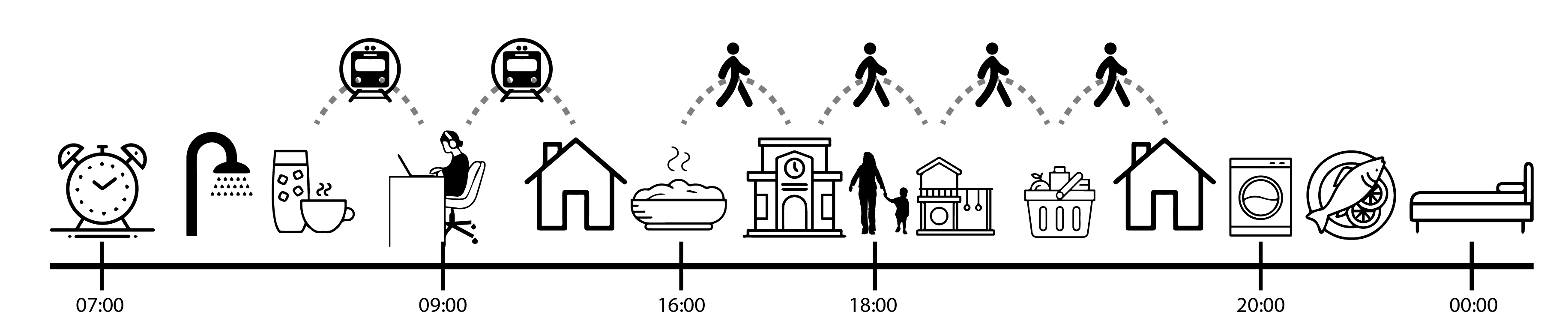

Adapting the city to the differentiated needs of the people living there also requires a reflection on travelling times. The Urban planning for everyday life emphasises that the various groups have different paces and experiences while using the city, which have to be taken into account when planning and managing it. A senior citizen moves around on foot at a different speed than an adult with toddlers and a pushchair, or someone in a wheelchair or an adolescent or young person. The distances and spatial needs that make a journey comfortable and safe are also different for each group.

Areas with conditioning factors

In regard to the study on mobility, according to the Urban Planning Manual for Everyday Life, placing life at the centre of policies means distributing public space by using the following hierarchy of importance: pedestrians, public transport, bicycles, goods transportation and private transport. It also means leaving an optimum pavement width of 3.6 metres without obstacles; adapting streets to a single-platform structure; abundant, safe pedestrian crossings that are coherent with mobility on foot and providing enough time so that people walking at different speeds can all reach the other side of the street; and clear, easy-to-read intersections, which favour visibility and therefore safety. In other words, the space where people move about must be a space for living.

In this study, we have selected data in order to define a series of conditioning factors for everyday mobility on foot, each of which has been assigned a score according to its impact. The analysis consisted of evaluating the presence of these conditioning factors for street sections and extrapolating the results to a neighbourhood scale, in order to make a territorial evaluation. The following table shows the conditioning factors taken into consideration and their associated scores.

| Conditioning factor | Score |

|---|---|

| Section pavement width of under 1.8 metres | 1 point |

| Section pavement width of under 1.8 metres and vehicles parked alongside | 2 points |

| Section pavement width of over 12 metres | 1 point |

| Sections that belong to one of the main very wide roadways (over 12 metres) with high traffic density | 2 points |

| Topographical gradient of the section of over 6% | 1 point |

| Sections located within a space that has a ‘large influx of tourists’ | 1 point |

On a general level, the map shows that a large proportion of Barcelona’s urban fabric has a low level of conditioning factors for people’s everyday mobility on foot. This is the case for nearly all the neighbourhoods in the Eixample, with the exception of Sagrada Familia, which has a medium level of conditioning factors due to its pavements being overcrowded with people visiting the Sagrada Família.

On a more detailed level, neighbourhoods with a high level of conditioning factors are mainly found at the boundaries of Collserola, Montjuïc and Els Tres Turons. We highlight the neighbourhoods of Can Baró, Vallcarca i Els Penitents, La Teixonera, El Coll and Les Roquetes, as the steep gradients combined with a lack of lifts in over half of the residential buildings (in Les Roquetes this rises to 85%) and the existence of metro stations that are not adapted for people with reduced mobility (the Vallcarca and Els Penitents stations) mean that the everyday dynamics of these neighbourhoods are affected to a greater degree.

The neighbourhoods of Sant Pere, Santa Caterina i la Ribera and El Barri Gòtic also have a high rate of conditioning factors for everyday mobility on foot. In these neighbourhoods, the journeys of local residents are not only affected by the large number of visitors walking around, but also by people who use city services or the tourist attractions which are concentrated in these areas. For local residents, the lack of a lift in their building can also limit their journeys; in the case of these two neighbourhoods, over half of the buildings lack a lift.

Lastly, the very high level of conditioning factors for everyday mobility on foot are found in three neighbourhoods: La Barceloneta, La Salut and Torre Baró. Three neighbourhoods with very different characteristics and dynamics, in which carrying out everyday tasks may mean a significant effort, or even an impediment, for people with reduced mobility, carers using pushchairs, senior citizens, etc.

Where are the people with the most conditioning factors for their everyday mobility on foot located?

There is no single answer to this question, because, according to the time of day, a person may be at home, at work or enjoying their free time in the street. The population moves around, and therefore determining ‘where they are located’ is something that cannot be resolved directly.

In this regard, in order to approximately identify the areas with the highest populations, regardless of the time of day, two sets of data have been employed: data from the municipal register of residents made it possible to delimit the areas with the greatest numbers of residents, while the data on facilities were used to identify the city areas that, potentially, are most used by the population.

Delimiting locations with the highest density of vulnerable people

In this case, the age groups observed, in terms of both facilities and population, were limited to children aged between 0 to 4 and senior citizens aged 75 or over. These two age groups are especially vulnerable to spatial conditioning factors in streets and squares (pavement width, roadway width, gradients, etc.).

The data used to localise these groups in the territory are as follows:

1) 1) The 2018 municipal register – which shows the areas with higher population density;

2) Public facilities – classified according to type and linked to age groups – to identify the parts of the city that may be more frequented by certain population groups.

The former were used to identify the areas with the greatest density of residents, broken down into age groups. The latter, meanwhile, were used to identify the parts of the city that are potentially most frequented by the different population groups. This is based on the hypothesis that the areas with the greatest concentration of mobility facilities intended specifically to be used by the age range in question are also those that are most frequented by said groups.

The aim of the exercise is to qualitatively highlight those areas that present a crossover of the highest values for exposure to conditioning factors, cross-referenced with the residential blocks that have an above average density of registered city residents and the areas with a high concentration of facilities serving the age groups under study.

However, it is necessary to state that there is no single answer to the question ‘Where are the people with the most conditioning factors located?’, as the population moves around according to the time of day, their work and the activities they carry out in their free time. It is therefore necessary to consider this as an approximation that endeavours to answer the question based on the available data. These are therefore large-scale maps and they must be contextualised by taking these aspects into account.

By cross-referencing the information on areas with the greatest concentration of everyday-mobility conditioning factors with the areas with the highest population density of vulnerable people – children aged 0-4 and senior citizens over 75 – critical locations of greater vulnerability were identified.

The coincidence of the three highest levels of conditioning factors (medium, high and very high) and the areas with the highest population density and concentration of facilities generates a vulnerability gradient that is summarised in the following six graphs:

| 1P. Medium level of conditioning factors coinciding with population density above the average |

| 1PF. Medium level of conditioning factors coinciding with concentrated population above the average and concentration of public facilities |

| 2P. High level of conditioning factors coinciding with concentrated population above the average |

| 2PF. High level of conditioning factors coinciding with concentrated population above the average and concentration of public facilities |

| 3P. Very high level of conditioning factors coinciding with concentrated population above the average |

| 3PF. Very high level of conditioning factors coinciding with concentrated population above the average and concentration of public facilities |

By selecting a particular age group, you can see the overlap between the areas with the highest level of medium-high and very high conditioning factors, and areas which have the highest population density and concentration of facilities.

In the analysis of everyday mobility on foot, according to the most vulnerable age groups, we can see that children aged between 0 and 4 are exposed to a medium level of conditioning factors in the neighbourhoods of El Raval, Sant Gervasi-Galvany, Sagrada Família, El Baix Guinardó, El Guinardó, Carmel, La Guineueta, La Prosperitat, Sarrià and Trinitat Nova.

In the case of senior citizens aged 75 or over, it is mainly the neighbourhoods of Poble Sec, Font de la Guatlla, Vallcarca i els Penitents and Montbau, where there is a population exposed to a high level of conditioning factors for everyday mobility on foot. The population of this age group exposed to a medium level of conditioning factors is most notably found in the neighbourhoods of Sagrada Família, El Guinardó, El Baix Guinardó, La Prosperitat, Horta, El Putxet i El Farró and Sant Gervasi-Galvany.

Related actions

Barcelona City Council has a long track record in turning Barcelona into a walkable city. The various street pacification strategies and actions (superblocks, widening pavements, protecting the school environments, etc.) make it possible to adopt modifications to the current distribution of public space, notably increasing the environmental quality of urban areas and enabling the introduction of new design concepts that improve comfort for itineraries on foot. Some notable examples of actions carried out in recent years include the superblocks in the neighbourhoods of Poble Nou and Sant Antoni, and streets giving priority to pedestrians.

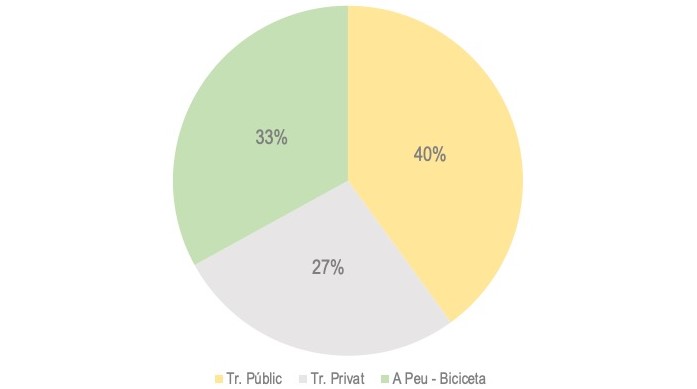

The measures favouring circulation restrictions on the most polluting vehicles also helped, such as declaring a 95 km2 area of the city as a Low Emission Zone and the recent implementation of a 30 kph speed limit on over 200 kilometres of city streets. These and other mobility planning and management measures in Barcelona, such as parking regulations, fostering public transport and promoting the use of bicycles, along with changes to the city model, all seek to mark the city’s political agenda with structural measures that have a positive impact on people’s health, the environment and, in general, on improving the quality of people’s everyday lives.

These transformations were accelerated due to the Covid-19 crisis, and the city’s public spaces have already moved towards increasing space for pedestrians and low-speed, sustainable personal mobility vehicles, which make it possible to ensure social distancing and contribute to progressively increasing the proportion of public space allocated to pedestrians. In this regard, the city has launched its Opening Up Streets programme, which consists of pacifying certain streets in the city on the first weekend of each month, turning them into open, healthy places that are free of fumes and become the scene of various activities for people to enjoy. The Protecting Schools programme has also been accelerated. There are plans for the City Council to take action on around 200 educational centres by 2023, gradually extending the programme to all of Barcelona’s schools, in order to improve and pacify their surrounding areas and ensure that they are safe and healthy places. Operations began at 22 city schools in the summer of 2020, and it is planned to make improvements to 50 more in 2021.

Along the same lines, for over 20 years Barcelona City Council has been working with city organisations, local and supramunicipal administrations, and bodies on the Barcelona Mobility Pact, which acts as a participatory forum and space for social consensus concerning the city’s mobility model, high-quality public spaces and a healthy city. More recently, in the context of Covid-19, three lines of action have been defined which favour healthy development, the economy and people’s social well-being. The new opportunities arising from the crisis favour a context where everyday mobility on foot becomes more important, and measures such as home working, flexitime and social awareness-raising on the impact of mobility in the city are key factors for accelerating a new, more efficient and sustainable model of everyday mobility for Barcelona and its Metropolitan Area.

Barcelona’s Resilience programme is a new opportunity to showcase the city’s current efforts in implementing structural measures aimed at improving everyday mobility. Measures such as promoting the Mobility on Foot Plan and the introduction of safe school environments, as well as others that promote disincentives for using private vehicles, such as imposing a 30 kph speed limit on 200 kilometres of city streets, are vital for fostering everyday mobility on foot, thereby helping to create more inclusive, people-friendly and healthy public spaces, maximising their potential for encouraging civic activities, relations and uses, helping to generate a more cohesive social and neighbourhood fabric which is therefore more resilient.